High blood pressure, high triglycerides and cholesterol, smoking, obesity, among others. They are the main factors related to atherosclerosis, a disease that leads to the formation and accumulation of fatty plaques in the arteries, gradually causing them to narrow and harden, leading in turn to obstructions or blockages of blood flow. What’s next? Heart attacks or strokes.

Beyond the habits and behaviors that can be detected and reversed, some of the causes are silent and capable of going unnoticed for a long time, only to become evident with a devastating and almost always irreversible event. This is the case of congenital traits, those characteristics or anomalies present from birth, and which often hide possible risks of various kinds. The possibility of understanding them in order to control or stop them is a question that excites scientists from all over the world, and these days an Argentine team celebrates an important finding achieved together with American colleagues and published in the Journal of Lipid Research.

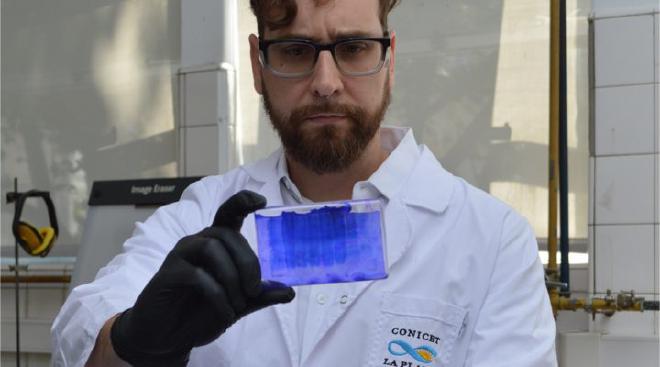

“From the time it was discovered in 1982 until now, it has not been possible to decipher the underlying cause that connects this mutation to the symptoms observed in patients,” said Ivo Díaz Ludovico, a CONICET fellow at the beginning of the research, and Marina González, a researcher at the organization, both at the Institute of Biochemical Research of La Plata (INIBIOLP, CONICET-UNLP).

While most scientific studies on the subject focused on thoroughly reviewing the functions of this protein, Díaz Ludovico and colleagues shifted the focus to its structure, and it was only then that, after subjecting it to a combination of advanced biophysics techniques and classical analyses, they detected the alteration that, they argue, would be the hidden cause of the failure in its functioning. According to González, “in the INIBIOLP laboratory, only some aspects of the function of the mutated protein had been studied and we had observed that it could not remove cholesterol from cells as the normal protein does.”

Currently, the reference techniques for the structural study of proteins – specifically X-ray crystallography or nuclear magnetic resonance – cannot be applied to APOA1 due to certain intrinsic limitations of the molecule. The INIBIOLP team then set out to develop different strategies and test other methodologies never before used to study this variant.

Thus, Díaz Ludovico contacted the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine of the University of Cincinnati, United States, a research space with vast experience in the study of structural problems of proteins, where they put into practice a chemical crosslinking followed by mass spectrometry, through which they were able to detect that the structure of this variant of APOA1 was abnormal compared to the native protein. that is, without the mutation.

The team has some hypotheses about what might happen next, although he clarifies that studies are still needed to prove or disprove them. On the one hand, they suspect that the protein in this state could be more prone to an uncontrolled interaction and, on the other, that it would not achieve the proper shape it needs to have to fulfill that function of “good” cholesterol.

Cardiovascular diseases are one of the leading causes of death in the world and, as already mentioned, their progression is slow and silent. Most of the reports of this variant of APOA1 correspond to people who have advanced atherosclerosis at a young age and without having risk factors such as obesity or hypertension.

Citation #

- The study The congenital APOA1 K107del mutation disrupts the lipid-free conformation of monomeric APOA1 and impairs oligomerization was published on the Journal of Lipid Research. Authors: Ivo Díaz Ludovico, Marina C. Gonzalez, Horacio A. Garda, Romina F. Vázquez, Sabina Maté, María A. Tricerri, Nahuel A. Ramella, Shimpi Bedi, Jamie Morris, Scott E. Street, Esmond Geh, Geremy C. Clair, W. Sean Davidson & John T. Melchior.

Contact [Notaspampeanas](mailto: notaspampeanas@gmail.com)